The ugly duckling

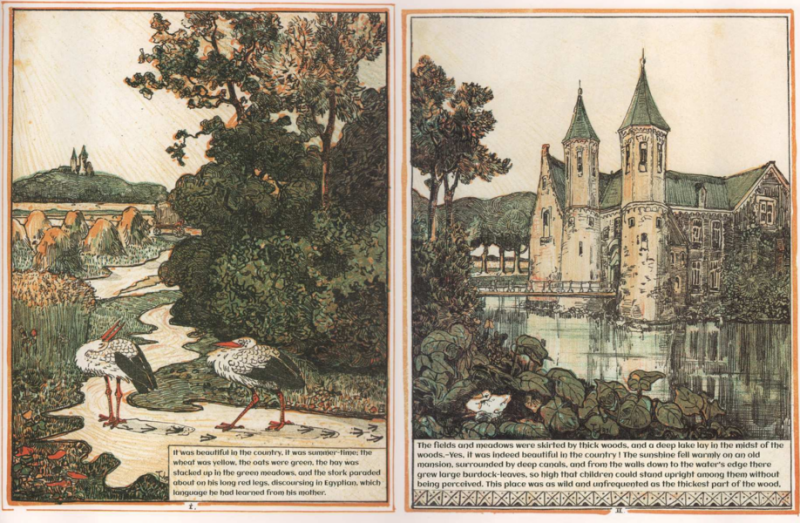

It was beautiful in the country, it was summer-time ; the sunshine fell warmly on an old mansion ; this place was as wild and unfrequented as the thickest part of the wood,

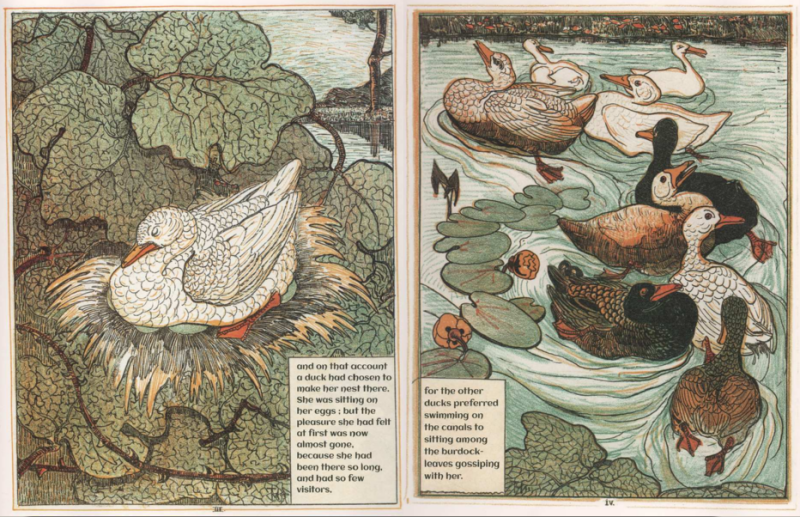

and on that account a duck had chosen to make her nest there and was sitting on her eggs ; but the pleasure she had felt at first was now almost gone, because she had been there so long, and had so few visitors, for the other ducks preferred swimming on the canals to sitting among the burdock-leaves gossiping with her.

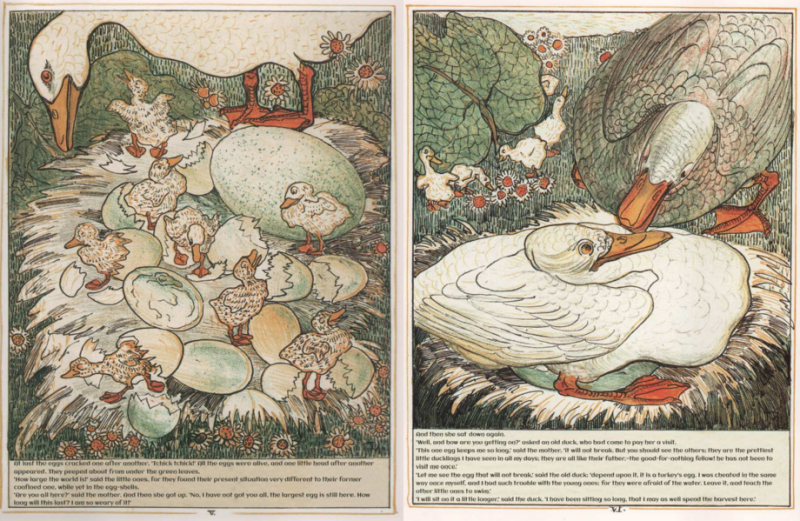

At last the eggs cracked one after another, 'Tchick tchick !' All the eggs were alive, and one little head after another appeared. 'Quack, quack,' said the duck, and all got up as well as they could ; 'Are you all here ?' and then she got up. 'No, I have'nt got you all, the largest egg is still here.' And then she sat down again. 'Leave it, and teach the other little ones to swim' said an old duck. 'I will sit on it a little longer,' said the duck. 'I've been sitting so long, that I may as well spend the harvest here.'

The great egg burst at last, 'Tchick, tchick,' said the little one, and out it tumbled—but oh, how large and ugly it was ! The next day there was delightful weather, and the sun shone warmly upon all the green leaves when mother-duck with all her family went down to the canal.

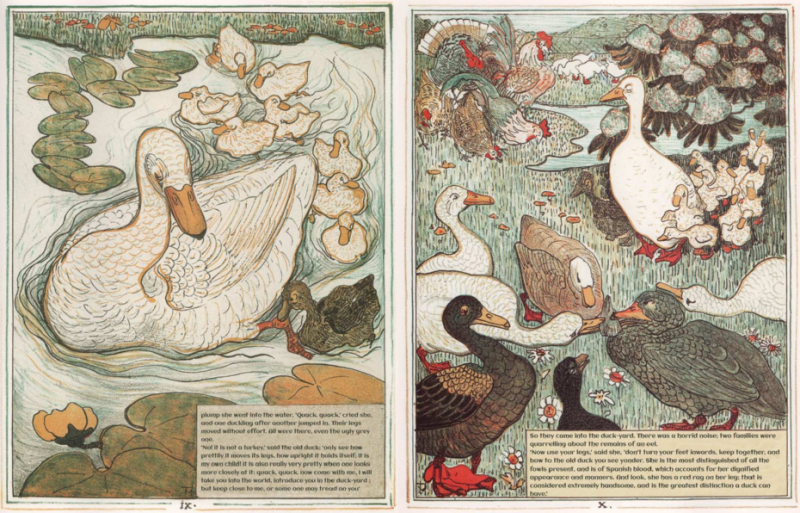

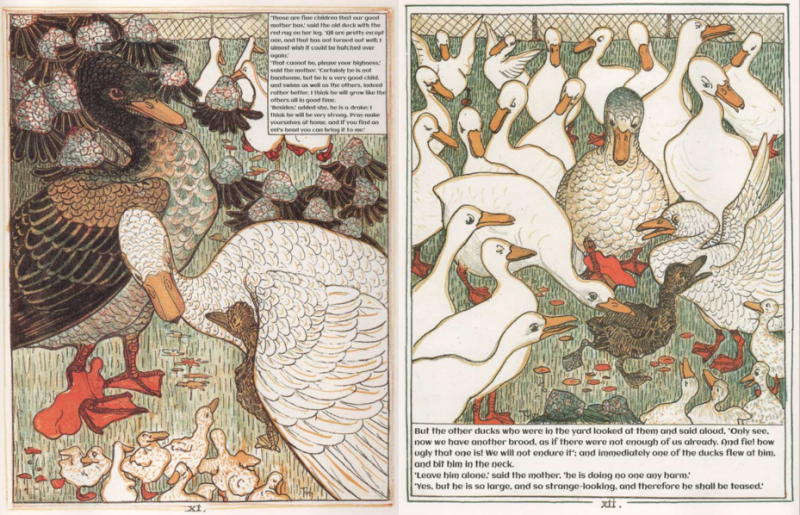

'Quack, quack,' cried she, and one duckling after another jumped in. 'Quack, quack, now come with me, I will take you into the world and introduce you in the duck-yard' ; 'Now use your legs,' said she, 'keep together, and bow to the old duck you see yonder. She is the most distinguished of all the fowls present. And look, she has a red rag on her leg ; that is considered the greatest distinction a duck can have.

'Those are fine children that our good mother has,' said the old duck with the red rag on her leg. 'All are pretty except one, and that has not turned out well ; I almost wish it could be hatched over again.' 'Certainly he is not handsome, but he is a very good child, and swims as well as the others, indeed rather better,' said the mother and she scratched the duckling's neck. But the poor little duckling, who had come last out of its egg-shell, and who was so ugly, was bitten, pecked, and teased by both ducks and hens.

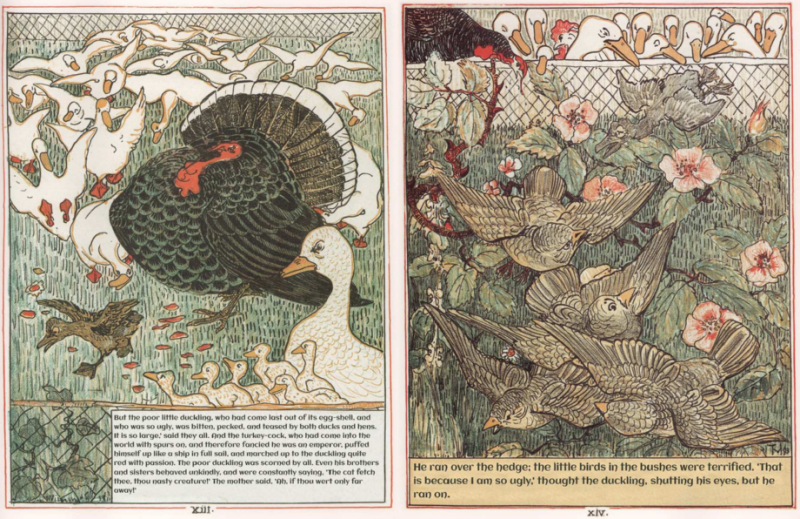

And the turkey-cock, who had come into the world with spurs on, and therefore fancied he was an emperor, puffed himself up like a ship in full sail, and marched up to the duckling quite red with passion. He ran over the hedge ; the little birds in the bushes were terrified. 'That is because I am so ugly,' thought the duckling, shutting his eyes, but he ran on.

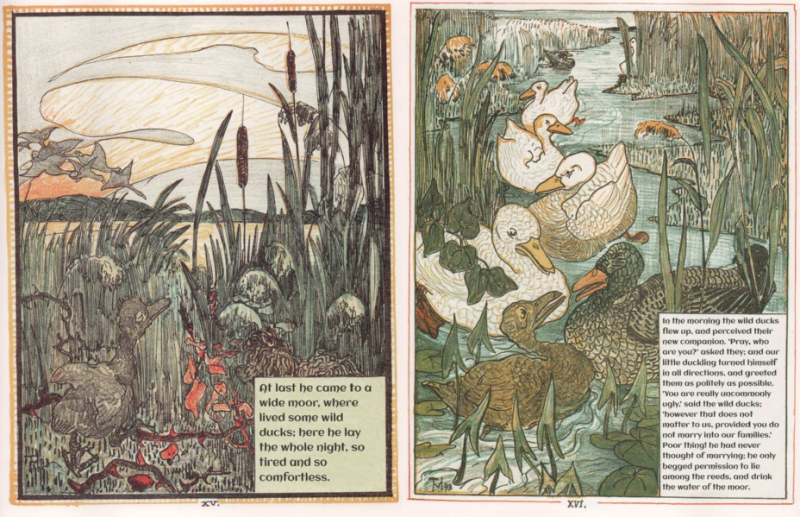

At last he came to a wide moor, where lived some wild ducks ; here he lay the whole night, so tired and so comfortless. 'You are really uncommonly ugly,' said the wild ducks ; 'however that does not matter to us, provided you do not marry into our families.'

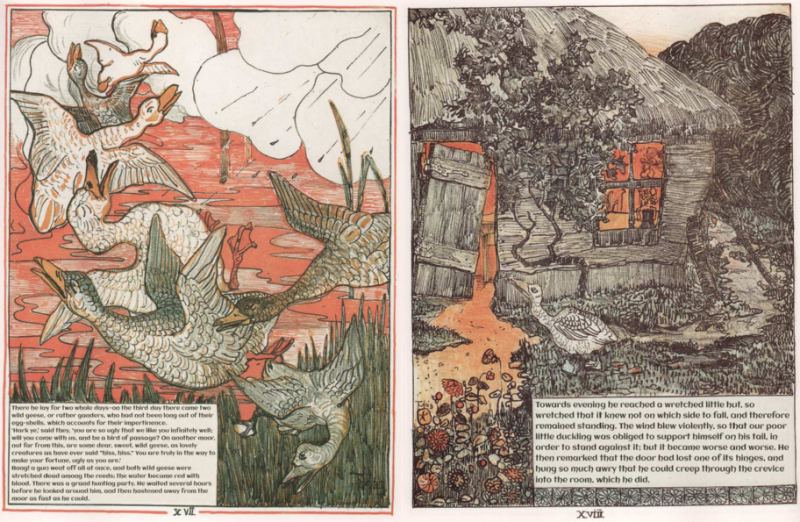

There he lay for two whole days ; on the third day there came two wild geese, or rather ganders, who had not been long out of their egg-shells, which accounts for their impertinence. Bang ! a gun went off all at once, and both wild geese were stretched dead among the reeds ; the water became red with blood. There was a grand hunting party. He waited several hours before he looked around him, and then hastened away from the moor as fast as he could. Towards evening he reached a wretched little hut, so wretched that it knew not on which side to fall, and therefore remained standing.

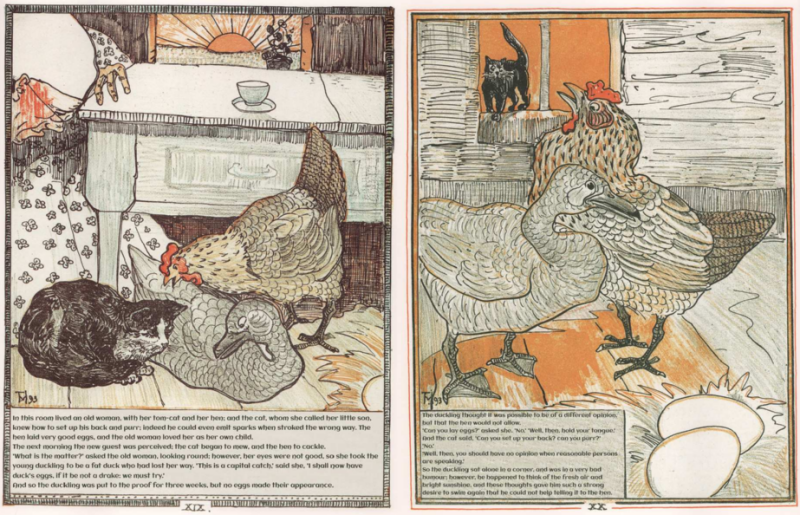

In this room lived an old woman, with her tom-cat and her hen ; and the cat, whom she called her little son, knew how to set up his back and purr ; indeed he could even emit sparks when stroked the wrong way. 'What is the matter?' asked the old woman, looking round ; however, her eyes were not good, so she took the young duckling to be a fat duck who had lost her way. 'This is a capital catch,' said she, 'I shall now have duck's eggs, if it be not a drake : we must try.'

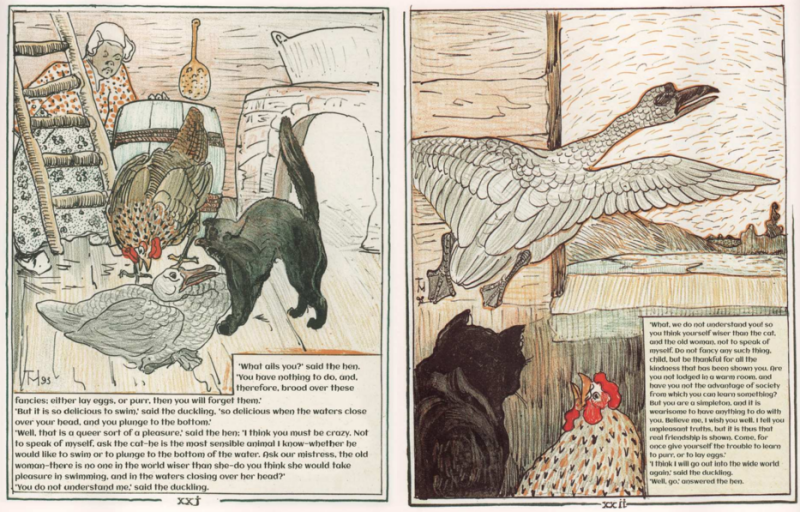

Now the cat was the master of the house, and the hen was the mistress, and they used always to say, 'We and the World,' for they imagined themselves to be not only the half of the world, but also by far the better half. So the duckling sat alone in a corner, and was in a very bad humour ; however, he happened to think of the fresh air and bright sunshine, and these thoughts gave him such a strong desire to swim again that he could not help telling it to the hen. 'I think you must be crazy. Not to speak of myself, ask the cat—he is the most sensible animal I know—whether he would like to swim or to plunge to the bottom of the water. Ask our mistress, the old woman—there is no one in the world wiser than she—do you think she would take pleasure in swimming, and in the waters closing over her head ?' 'I think I will go out into the wide world again,' said the duckling. 'Well, go,' answered the hen.

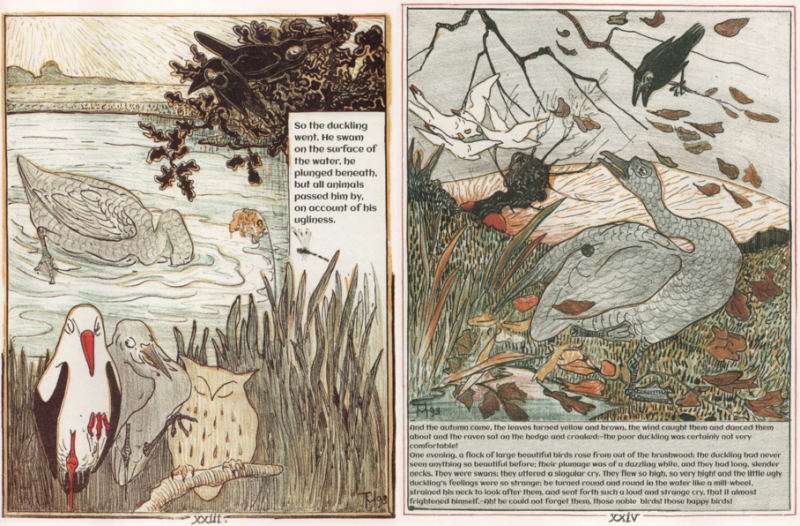

So the duckling went. He swam on the surface of the water, he plunged beneath, but all animals passed him by, on account of his ugliness. And the autumn came, the leaves turned yellow and brown, the wind caught them and danced them about, and the raven sat on the hedge and croaked ; the poor duckling was certainly not very comfortable ! One evening, just as the sun was setting with unusual brilliancy, a flock of large beautiful birds rose from out of the brushwood ; the duckling had never seen anything so beautiful before ; their plumage was of a dazzling white, and they had long, slender necks. They were swans ; they uttered a singular cry and the little ugly duckling's feelings were so strange ; he turned round and round in the water like a mill-wheel, strained his neck to look after them, and sent forth such a loud and strange cry, that it almost frightened himself.

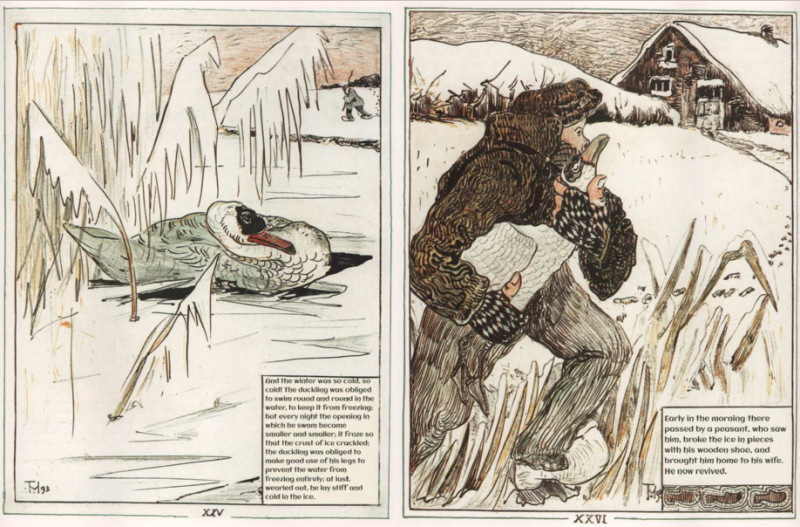

And the winter was so cold, so cold ! The duckling was obliged to swim round and round in the water, to keep it from freezing ; it froze so that the crust of ice crackled ; at last, wearied out, he lay stiff and cold in the ice. Early in the morning there passed by a peasant, who saw him, broke the ice in pieces with his wooden shoe, and brought him home to his wife.

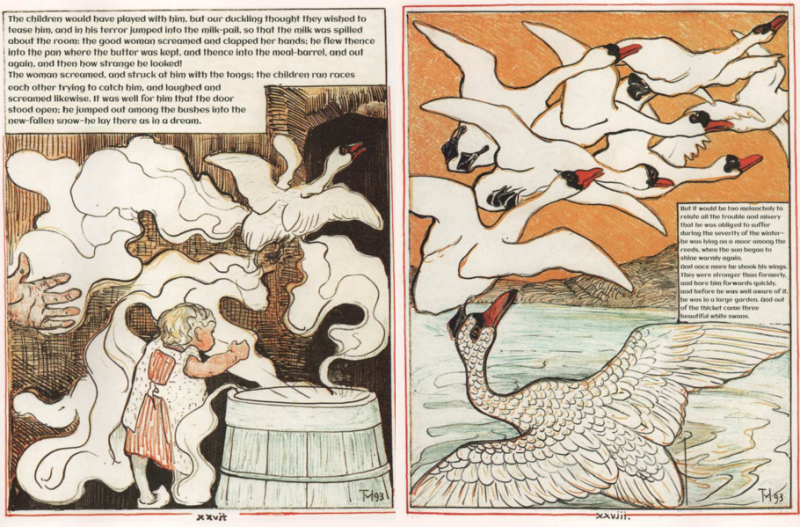

The children would have played with him, but our duckling thought they wished to tease him, and in his terror jumped into the milk-pail, so that the milk was spilled about the room: the good woman screamed and clapped her hands ; it was well for him that the door stood open ; he jumped out among the bushes into the new-fallen snow and lay there as in a dream. When the sun began to shine warmly again, when the larks sang, beautiful spring had returned. And once more he shook his wings. They were stronger than formerly, and before he was well aware of it, he was in a large garden and out of the thicket came beautiful white swans.

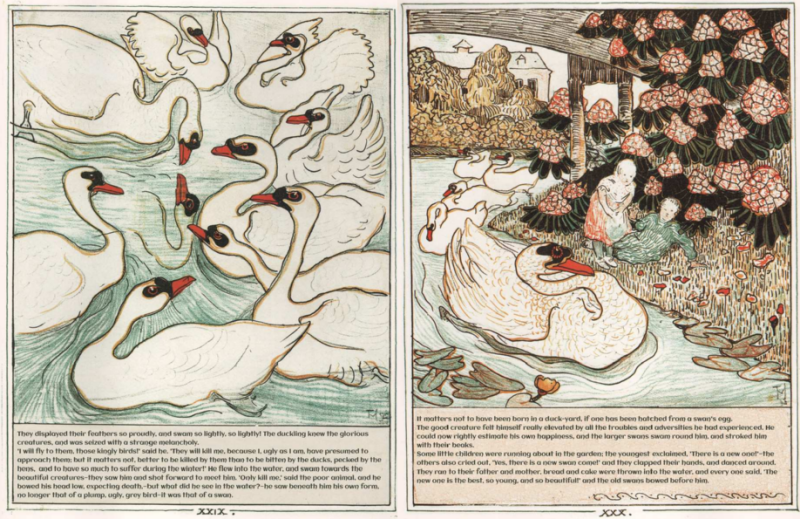

He flew into the water, and swam towards the beautiful creatures—they saw him and shot forward to meet him. 'Only kill me,' said the poor animal, and he bowed his head low, expecting death,—but what did he see in the water?—he saw beneath him his own form, no longer that of a plump, ugly, grey bird—it was that of a swan. Some little children were running about in the garden ; they threw grain and bread into the water, and the youngest exclaimed, 'There is a new one!' 'The new one is the best, so young, and so beautiful !' and the old swans bowed before him.

The young swan felt quite ashamed, and hid his head under his wings ; he scarcely knew what to do, he was all too happy, but still not proud, for a good heart is never proud.

The_ugly_duckling

Auteur (images): Theo Van Hoytema

Auteur (bande son): Annie Lesca

Licence:

Ce diaporama a été produit à l'aide du logiciel Raconte-Moi d'AbulÉdu et utilise le travail de Atul Varma (sous licence cc-by) pour la partie web.